Declaration of Independence - John Trumbull (1818)

In my last post, I wrote about a particular American story—the story of America’s deep rooted opposition to tyranny. In this post, I am investigating another American story—and asking a series of questions about America’s founding in religion.

The reason I am interested in America’s founding relationship with religion is its seemingly critical relevance to the cultural conversation about (1) what is wrong with America today and (2) what is needed to fix America today. The argument about the necessity of religion often goes like this:

America was founded on religion; i.e. American systems require religious values as a “necessary substrate” to function properly

The modern age has stripped us of religious values; this explains why modern America is struggling

To restore America to its past greatness means restoring religion in its people.

The whole argument hangs on that first premise—that “American systems require religious values as a necessary substrate to function properly.” This is often taken to refer to Christianity in particular.

Prior to writing this piece, I didn’t feel that I had a solid grip on the answer. Nor did I feel convinced by conversations. Answers were often vague. Those who were convinced that Christianity was critical would say things like: the founders were all Christians; the Pilgrims were puritans; In God We Trust is written on our money; obviously we are a Christian nation. Others would say the opposite: America was founded on freedom of religion and separation of church and state is a core principle; obviously we are not supposed to be explicitly religious. So, in this post, I am hoping to better understand the question: Was America founded on religion? And more specifically, did the founders see religion as a necessary substrate for the American system to function properly?

To begin with, there is no smoking gun in favor of religion

When I set out to investigate these questions of religion and the founding, I didn’t know exactly what I would find. In the course of writing this piece, I’ve found a lot of surprising things. One thing I have not found is a smoking gun that indicates that the American system was founded on religion.

Let me give you an example of what I think is a smoking gun for a country founded on religion: Iran. The official name of Iran is the “Islamic Republic of Iran.” It describes itself as a “unitary theocratic republic.” It’s constitution mentions Islam more than 200 times. Here is article 1, i.e. the first content of the document, hot out of the gate:

The form of government of Iran is that of an Islamic Republic, endorsed by the people of Iran on the basis of their longstanding belief in the sovereignty of truth and Qur'anic justice, in the referendum of Farwardîn 9 and 10 in the year 1358 of the solar Islamic calendar, corresponding to Jamadial-'Awwal 1 and 2 in the year 1399 of the lunar Islamic calendar [March 29 and 30, 1979], through the affirmative vote of a majority of 98.2% of eligible voters, held after the victorious Islamic Revolution led by the eminent marji' altaqlid, Ayatullah al-'Uzma Imam Khumayni.

Whatever else you may think about Iran, there is no ambiguity as to whether this is a religious state. It’s not even controversial to state this. It’s self-evidently and proudly true in the first article of its constitution. Imams rule Iran, including the supreme ruler who has political and ideological control over the country.

Now, just because the U.S. is not ruled by a Catholic Bishop doesn’t mean it isn’t fundamentally Christian. Nor does it mean that religion was not important in the founding. The reason I mention Iran is because it provides an example of one end of the spectrum that is “definitely religious.”

By contrast, the American system is at least less explicitly religious than Iran. But, how much less? Answering this question is going to require a little more digging. And since we have just caught a glimpse of an explicitly religious constitution, let’s flip over and look at the U.S. constitution. What does the U.S. constitution say about religion?

The U.S. constitution mentions religion twice

First of all, the U.S. constitution never once mentions Christianity. And there is only one mention of religion in the original US Constitution. It comes in article 6:

The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.

Basically, it’s right there in the beginning that anyone of any religion is allowed to hold office and that no religious test shall ever be required. So, even if we were to believe that religion is “a necessary substrate for the American system,” the founders made clear that under no circumstances are we allowed to select for it in our leaders. Ok, so the leaders of America are out—they can be whatever religion (or lack of religion) they want. But, what about the people? One might make the case that, while leaders need not be selected for their religious beliefs, it is still critical for the people themselves to be religious.

Well, The Bill of Rights, which as you may also remember is the constitution (it is the first ten amendments to the constitution) also includes a provision protecting the freedom of religion in the people. This, of course, is the first amendment:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The first amendment thus adds to Article 6 and says that congress shall do nothing to either restrict OR assert any kind of religion. Here again, even if we determine that religion is “a necessary substrate for the American system,” perhaps for the broad citizenry of the country such that they will behave in a proper way, the first amendment makes clear that congress is not allowed to assert any kind of religion upon them or restrict any kind of religion that they are allowed to practice.

Besides these two instances, there are no other mentions of religion and not a single mention of God in the entire document (more on that in a moment).

At this point, just with the U.S. constitution, the founders have established for us that it is not legal for any of our leaders to be selected on the basis of religion or for any religion to be asserted upon its citizens. So, if the premise that “American systems require religious values as a “substrate” to function properly,” is possibly true, then the religious values must necessarily have been hidden elsewhere or implicit in the founding.

State constitutions mention God.

After the U.S. constitution, the next best place to look for principles in the founding of America is in U.S. state constitutions. And while the U.S. constitution does not mention God a single time, the state constitutions mention God, Lord, Almighty, or the Divine quite a bit. This map was put together by the Pew Research Center to show just how many times.

But, before you start sayin’ your Hail Marys about how you knew we were a Christian nation all along, let’s look at what these state constitutions actually say. Most substantive references to “God” in state constitutions are in the preambles of the state constitutions. For example, California’s preamble reads:

We, the People of the State of California, grateful to Almighty God for our freedom, in order to secure and perpetuate its blessings, do establish this Constitution.

All 50 states do something similar. And, looking back at the Pew Research Map, the preambles explain why every state constitution has at minimum 1 mention of God. It turns out that nearly all of the other references to “God” or “Lord” or “Almighty” or “Supreme Ruler of the Universe” in state constitutions are either to note that there will be no restrictions on what God anyone wants to worship or to mention “the year of our Lord” to note the current year. So, we can’t really take any of this to be an explicit endorsement of religion.

However, you could say that these preamble references are still implicitly important for legitimizing the state or anchoring it in history, tradition, or even Christianity. Maybe this is true. I don’t see any way to dispositively disprove this interpretation.

However, there is some legal evidence that U.S. preambles would be interpreted as “patriotic” rather than “religious” nods to God.1 I’ll get into this more later in this piece, but it turns out that the language of the Pledge of Allegiance (which contains a similar nod to God) has been challenged in both state and federal courts under the argument that it forces people to use religious language in violation of religious freedom. These challenges have been struck down several times on the basis that the Pledge’s nod to God is not a religious assertion but a patriotic pledge indicating the universal importance of the assertion.2

The U.S. and its states have 51 constitutions, and only 1 does not mention God

What’s perhaps most interesting about the state constitutions is that they further spotlight how unique the U.S. Constitution is by not including God in its preamble. The secretary during the Constitutional Convention, Charles Thompson (remember that name; it will come up later), wrote in his notes that there was great debate about whether to include “God” in the Constitution, but the decision was made to explicitly leave Him out. I.e. it wasn’t an accident that “God” doesn’t appear in the U.S. constitution, and it wasn’t a unilateral decision. There wasn’t even a 3/5 type compromise to include the son but not the father or something like that. “He” was explicitly and entirely excluded.

So, again, if religion is indeed “a necessary substrate” for the U.S. system, then the founders must have believed that something outside of the official documents would ensure and perpetuate the role of religion in American society.

One hypothesis is that religion at the founding was so pervasive and so entrenched that no one questioned whether it would persist. In this view, James Madison, the father of the U.S. constitution, and all of the other founders explicitly left God out because they didn’t think it was necessary to mention Him.

If this is true, then a relevant question would be: how religious was America at that time? And more specifically, how religious were the founding fathers?

There is huge debate about the religious beliefs of the founding fathers

First of all, let’s get atheism out of the way. The most obvious and undisputed atheist of the founders was Thomas Paine. You may remember from high school U.S. history that Paine wrote the pamphlet Common Sense, the 1776 version of a tabloid bombshell that called for independence from Britain and set the colonies on track for the revolutionary war. After the revolution, he wrote extensively about reason and freethought and argued strongly against religion and Christian doctrine in particular.

So, one confirmed atheist. But, as far as I can tell, he seems to have been the only one for which there is no question.

Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe all at least went to Christian churches. But, they also seem to have had odd relationships with religion. Some didn’t pray or take communion. Some have surviving letters that read more like an 18th century Richard Dawkins than a Jerry Falwell. Some liberal outlets say all these men were all Deists—a form of Christianity that asserts that reason is more important than revelation and that rejects things like the virgin birth, original sin, and the resurrection of Jesus. Conservative Christian outlets say, “no they weren’t!” Others say, it’s complicated and that we have no real way of knowing because their terms don’t really match ours. In my amateur opinion of having read about this stuff for the last few months, I’m more convinced that they were probably deistic, and over the rest of this piece you’ll see a bit more of why I think this.

But, what’s interesting to me about the question of the personal religion of the founders is that those arguing that “religion is a necessary substrate” seem ready to die on this hill. They lean heavily on the founders themselves being Christians and there are seemingly hundreds of websites devoted to proving this. I find this interesting because it seems to me that even if all of the founders were religious, I don’t think it is a dispositive finding about the necessity of religion for America to function.

I also think the Christian ties are confounded by another aspect of these guys’ personal, moral lives that’s worth mentioning.

All aboard the freemason express

The most interesting finding I came across, in the realm of personal ethics, was that several founders, including George Washington and Ben Franklin were well known freemasons, an organization made famous to the millennial generation by the movie National Treasure and a whole series of Dan Brown novels. But what are the freemasons exactly?

Britannica describes the freemasons as a fraternal, oath-bound, secret society that emphasizes ethics through reason (sounds kinda deistic eh?). At the time of the founding, the freemasons were famous for questioning religious dogma, opposing the clergy, and asserting a morality based in reason, independent of Christianity. Because of this and because of their quasi-religious teachings and rituals, they were embroiled in conflict with Christianity.3

The connection of the founders and the freemasons isn’t just Hollywood speculation either—it is widely acknowledged. In 2007, the U.S. House of Representatives passed Resolution 33 that explicitly stated that the founders were freemasons:

Whereas the Founding Fathers of this great Nation and signers of the Constitution, most of whom were Freemasons, provided a well-rounded basis for developing themselves and others into valuable citizens of the United States…

There is also evidence of this in our founding documents. I’ll start with an especially fun one. Remember above when I told you that every U.S. state preamble includes “God” in the title. Well, several them actually state “Supreme Ruler of the Universe.” Here is Colorado’s preamble:

We, the people of Colorado, with profound reverence for the Supreme Ruler of the Universe, in order to form a more independent and perfect government; establish justice; insure tranquility; provide for the common defense; promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution for the "State of Colorado".

Why would anyone write this instead of simply “God”? Turns out, the main group that uses the term “Supreme Ruler of the Universe” is the freemasons. In fact, they require their members to pledge belief in “the existence of a Supreme Being and in the immortality of the soul.” They also call Him the “Great Architect of the Universe” (G.A.O.T.U.).

The people who influenced the founders were clearly atheists

In some sense, we might want to give the founders a free pass on their rationalistic and potentially-deistic personal views. The latest, hottest thinking of that era was rational enlightenment thinking, and it was not cool for educated men to believe in superstition. Here I’m referring to the famous enlightenment liberals of Europe who so greatly influenced the founders.

Thomas Pangle writes that it was the explicit goal of these guys—the first wave modern political theorists (Spinoza, Locke, Montesquieu)—to reduce the influence of religion on politics. Leo Strauss writes that Hobbes and Locke were probably atheists4 —that Hobbes wrote his Leviathan because he was disgusted with the senselessness of religious war and wanted to engineer men out of the state of nature and into something more civilized—that Locke used Bible references in his Second Treatise, but apparently only as a way to convince the religious mainstream to accept his non-Christian ideas on individualism and property.5

Rousseau also seems to have shown his hand in Discours sur l’inégalité (Discourse on inequality) where he wrote how a small number of rich or intellectually gifted people (i.e. the elite) may not need religion, but that the ignorant masses would have nothing to sustain their lives if they didn’t have a belief in the afterlife.

Rousseau, as I’ve quoted him here, provides one potential argument for the tacit importance of religion “as a necessary substrate” in the founding of America. I.e. that, while the elites (the founders) might not need it, the so-called ignorant masses do. Maybe the founders thought this, but if they did, they didn’t write it into any of their documents. As I told you in the beginning of this piece, the first Amendment explicitly prevents the government from asserting any religion upon the people.

This provides another interesting contrast of the enlightenment liberals with the founders. Whereas Locke used Bible verses in his Second Treatise to “placate the masses,” the founding fathers of America seem to have had a haughtiness, hubris, or at least confidence not to pander to a “Christian nation” and not to include any explicit mentions or references to God or Christianity to justify their Constitution. In fact, they seem to have explicitly excluded these mentions (as secretary Charles Thompson noted)—presumably, and this is my interpretation of the situation—because in their new age and in their new country, they had the license and mandate to assert a political system based solely in enlightenment reason.

In America, religion is subordinated to liberty

The result is the subordination of religion to liberty. This is the enactment of enlightenment thinking. This is the point. It is the pinnacle of 18th century intellectualism. Vive la liberte. Maryland’s constitution provides an example:

“Religious liberty [is granted] unless, under color of religion, any man shall… infringe the laws of morality, or injure others, in their natural, civil, or religious rights.”

This means is that, when push comes to shove, individual liberty trumps religious values. In essence, this distinction is what makes the U.S. not a theocracy. In fact, it’s a big part of what makes the U.S. “liberal” at all.

Here is an example of this in practice. Let’s say you are Somali. You move to the U.S. with your young daughter. Let’s say, based on your religion, you view it as your duty to have her circumcised. Problem is, in America this is called FGM and it is illegal under The Federal Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act. In fact, it’s also illegal to send or attempt to send her outside of the U.S. for FGM. In our system here in America, your personal religious rights, even regarding someone as close as possible—your own daughter—are limited by the overwhelming firepower our country grants to her personal liberty.

Remember in the beginning of this piece when I told you about the Islamic Republic of Iran? They not only allow FGM, it is illegal under their constitution to pass a law against it.

Here’s another example, this time from Pakistan, another Islamic Republic, where the law of God is put above individual liberty. A few years ago, a guy killed his sister for “disgracing herself in the eyes of God” by posting lewd photos on social media. He confessed to it and yet he was not prosecuted in any way. It was deemed an “honor killing.” In America, as the founders intended, the guy would be in jail for murder.

The Declaration of Independence

Ok, so there is one document I have skipped so far. It’s the Declaration of Independence, and it does include several mentions of “Nature’s God” and “Creator.”

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Superficially, these sound like references to an unspecified religion. But, as I’ve shown you with the language of the freemasons, it’s not always so clear that the founders were talking about the God of Abraham. And as I’ve written in previous posts, we should be suspicious of Locke, the founding fathers, and their “self-evident truths” because they are all pedaling versions of modern natural right—a natural right ostensibly rooted in God but based in the relative aims of the age, which in the age of modernity are not in the transcendent rights of divine revelation but in the temporary whims of the day.

For example, the UN declaration of human rights also holds "truths" to be self evident. I'd say that this document — a liberal post-war manifesto — is no endorsement of God or what is natural. It is pure ideology wrapped in a façade of universal legitimacy. This is the crisis of modern natural right. It’s the replacement of “natural right” with “ideology” under the auspice of a “divine ruler of the universe” or “nature’s God” or whatever term you want to use. The Declaration of Independence decidedly did not state “The God of Abraham.” It simply wrapped liberal ideas in a façade of “Nature’s God.”

Which brings me to one more piece I wanted to touch on: the explicit mention of Christianity. I was curious if I could find any references at all to Christianity in any of the founding documents. Here is what I found.

The Treaty of Tripoli

One of the first U.S. treaties was the Treaty of Tripoli with what is modern day Libya. The intent of the treaty was to ensure safe trade for U.S. ships in the Mediterranean sea. This was tricky because Libya was and is a predominately Muslim country, and America did and does have lots of Christians in it. So the issue of religion was potentially something to sort out. The founders, however, didn’t think this was anything to worry about. Here is article 11:

As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion — as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen — and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

This was passed unanimously by the U.S. Senate in 1796 and signed by President John Adams.

Naturally, this document is is cited as evidence that America is not a Christian nation. It’s a pretty definitive statement.

But, before we give up, let me show you one instance of a positive assertion of Christianity on an early draft of the U.S. seal.

Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God

At some point in your life, you will have no doubt seen the Seal of the United States. It’s kind of like the U.S. coat of arms. It was and still is used for marking official treaties, presidential letters, executive orders, and communications with foreign nations. Similarly, it is still used on our currency, your passport, government buildings, airforce one, and the presidential lectern.

What I’m showing you here is only the front of the seal (spoiler, there’s a back also). And on first glance, it’s not a very religious symbol. But, let’s look more deeply at its origins.

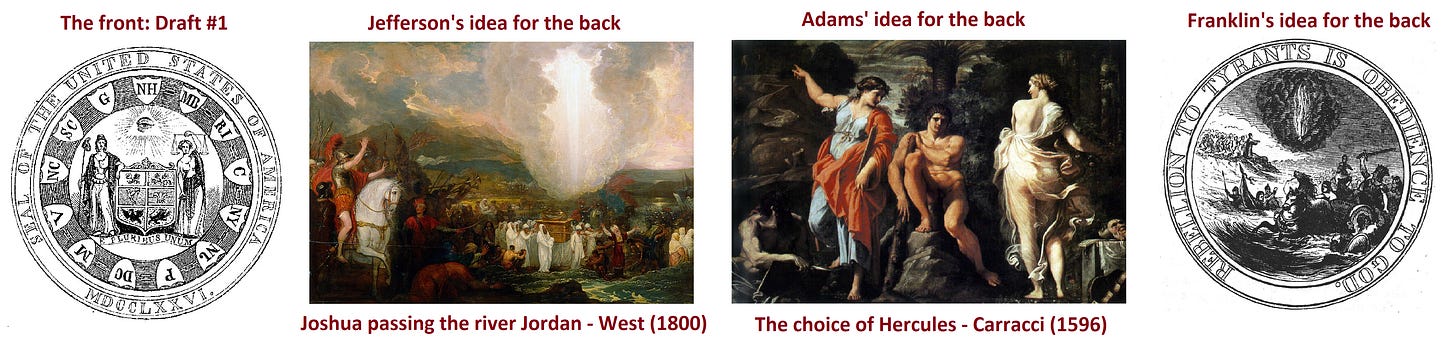

It all began on July 4, 1776, the day the U.S. declared independence from Britain. That same day, the assembly of founders decided they also needed an official national symbol to mark official documents. So they formed a committee of three people to create a seal: Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams. Here’s where it gets religious and Christian:

Jefferson wanted to depict the children of Israel in the wilderness led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. Adams wanted a rendering of the “Judgment of Hercules” which depicts the young Hercules deciding whether to take the path of self-indulgence or the difficult, rugged, uphill path of duty.6 Franklin wanted to use an allegorical scene from Exodus. He described this scene in his notes as:

Moses standing on the Shore, and extending his Hand over the Sea, thereby causing the same to overwhelm Pharaoh who is sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his Head and a Sword in his Hand. Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Clouds reaching to Moses, to express that he acts by Command of the Deity. Motto, “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God.”

I’ve only found a rendering of the front and of Franklin’s idea for the back but have included here paintings of Jefferson’s and Adams’ ideas just to show you what they were going for.

Let’s start with the draft for the front side of the seal. You can see the thirteen states as well as a woman (liberty) and man (strength). Above them is the Eye of Providence—the all seeing eye, which in Christianity is sometimes associated with divine providence. It can be found in Christian art and on Churches symbolizing God's omnipresence.

As for the back, Jefferson and Franklin’s ideas are obviously direct religious stories from the old testament. Franklin’s is also a great nod to my last post about how the founders were more obsessed with their opposition to tyranny than they were in their commitment to freedom.

Unfortunately however, in the case for religion, Congress didn’t like these ideas and rejected them. A few years passed before they created a second committee. But congress didn’t like the second design either. Or the third. Finally, congress turned to the Secretary Charles Thomson (remember him?!) who took various elements from the three previous committees and created the seal that we know today. This final version was adopted in 1782.

I’ve already shown you the front of the seal, but maybe you know that the back of the seal is also found on the USD.

The front of the seal is pretty irreligious. It is the bald eagle, with its thirteen arrows, olive branch, thirteen stripes, and the phrase E pluribus unum, which means, “out of many, one." The significance of this phrase is that, in the founding of the U.S., the thirteen colonies came together to form one body in rising up against the tyranny of England.

But, the back of the seal, while not the original Christian vision of Jefferson or Franklin, seems at least somewhat religious, right? The first phrase “annuit cœptis” means “I approve, I favor,” which in the context of the Eye of Providence means something like “I, providence, favor these undertakings.” The second phrase “novus ordo seclorum,” means, “new order of the ages.” Put together, the reverse of the seal might be read as an indication that providence favors the new order of the ages. (By the way, the pyramid has thirteen layers, indicating the original 13 states).

However, the guy who created this, Secretary Charles Thompson was, like many of the other founders, a freemason. And the pyramid and the eye of providence are more extensively linked to the Illumanati and the freemasons than they are to Christianity. Again, what’s interesting to me about this is that Congress rejected all of the explicitly religious versions of the seal that were offered in versions one, two, and three. And they ultimately settled for a version that is more linked to the freemasons and the Illumaniti than to Christianity.

Ok, let’s try the next religious aspect of the dollar: “In God We Trust.” Where did this come from?

The slow creep of God in the 20th century

Turns out, E Pluribus Unum was never an official motto—it was just a de-facto motto, taken from the seal. In fact, the U.S. did not have an official motto until 1956 when Congress passed a law, signed by Dwight D. Eisenhower, to make the new motto “In God We Trust.” 7

The timing was not an accident. The cold war was heating up and U.S. was positioning itself as a counter to the explicitly atheistic Soviet Bloc. I.e., the legislation to put God into the picture with an explicit motto was a tactical public relations move. The representative Charles Edward Bennett, a democrat from Florida who put forward the bill to create the motto put it like this:

“[in] these days when imperialistic and materialistic communism seeks to attack and destroy freedom, we should continually look for ways to strengthen the foundations of our freedom”

Bennett here is implying that our freedom is tied to our trust in God. But if God were so important for ensuring our freedom, why did Congress wait until the 20th century to make it our motto? I’ll let you ponder that.

One Nation Under God

A similar story played out with the Pledge of Allegiance. The pledge was written by Francis Bellamy in 1892. Here is the original version:

I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic, for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

Notice anything? First, it states “my” flag. Bellamy thought this was good because it could be used by any nation. But, when a whole bunch of immigrants came to the U.S. in the 1920s, there was a big push by the American Legion and the Daughters of the American Revolution to specify the allegiance as being to the U.S. flag. That was the first change—changing “my flag” to “the flag.”

But you probably also noticed that the original version did not contain the phrase “under God.” This phrase seems to have first been added by the Knights of Columbus in 1951. And, once added, it spread quickly. In 1954, President Eisenhower’s Presbyterian pastor delivered a sermon based on the Gettysburg Address entitled “A New Birth of Freedom” that made a case for including “under God” in the pledge. It is said that this speech convinced Eisenhower to make it happen. Within four months, congress passed a law adding the phrase and Eisenhower signed it into law. Said Eisenhower:

From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural school house, the dedication of our nation and our people to the Almighty.... In this way we are reaffirming the transcendence of religious faith in America's heritage and future; in this way we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country's most powerful resource, in peace or in war.

The text of the pledge was now the one that we all recognize:

I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

With the motto and the Pledge of Allegiance, God was being added to the essence of America. It was being added at a time when worldwide communist atheism was on the rise and when religion itself was undergoing mass upheaval. And it was happening at a time when Americans themselves were becoming less religious.

The 1960s

Major social and religious changes played out in the 1960s. There were new drugs, changes in the way people dressed, use of bad language, new views about sex, opening of sexual mores including more pre-marital sex (enabled by birth control), and new sexual acts. There was newfound atheism and disconnection from traditional family values. Jack Kerouac ushered in this new age with On the Road and The Dharma Bums. Joan Didion’s works, including Slouching Toward Bethlehem, chronicled (1) what was so different and (2) morally detestable about this new age.

The Civil Rights movement and Vietnam War made people re-think values. The Catholic Church went through Vatican II as a way to “update” its processes to better connect with an increasingly secular world. Timothy Leary glamorized psychedelics. Elvis’s “vulgar” onstage gyrations outraged critics. Women were increasingly liberated.

The reason I mention all of this moral upheaval is that it opened up a division between voters who welcomed the new age of “enlightened” (lax) mores and those who felt a traditional religious morality slipping away from them.

America was beginning its modern political schism. Previously, people had held different moral views, but almost everyone was Christian. Now, only some people were Christian. Others were dropping like flies. This had political implications.

The Moral Majority

As America became less religious, it did so unevenly. This continues to play out. Liberals are more likely to have left religion than conservatives. And in a world of thin political margins, this makes for juicy hunting ground for political strategists.

In the 1970s Jerry Falwell, a Baptist Minister and megachurch titan from Lynchburg VA, began touring the country and giving sermons and speeches on Christian moral issues. It was wildly successful and he soon became a household name. Riding this wave, he founded the Moral Majority in 1979, a political organization of the Christian Right that supported socially conservative and traditionalist policies. He and other Conservative Christians were not happy with the social change of the 70s, including legalization of abortion in 1973 and the first evangelical Christian president, Jimmy Carter, who had done little to oppose these changes. The Moral Majority threw its new weight behind the republican challenger Ronald Regan, and is thought to have been decisive in Regan’s 1980 victory over Carter.

A new age had begun. When the Moral Majority was dissolved in 1989, Falwell apparently said, “Our goal has been achieved... The religious right is solidly in place and [...] religious conservatives in America are now in for the duration.” This connection of Christianity and the right has held ever since.

Even Donald Trump—far from being any kind of practicing Christian—just released a Trump Bible in the lead up to the 2024 election, something we have not seen democratic leaders do. And if you’re thinking, “why would they, they’re just a bunch of atheistic heathens,” then yes, that’s the point.

The reason I am emphasizing the modern connection between the right and Christianity is because this connection makes it more likely than ever that conversations about “the role of religion in America” will be laced with political motives. If ever the question of religion in America were non-partisan, it is decidedly not today.

What does it all mean?

When it comes down to it, the question I posted at the start of this piece about the American system requiring a “religious substrate” need not be proven, only be disproven. It doesn’t really matter whether the founding of the U.S. is explicitly irreligious, only that it is not explicitly religious. And the evidence for this seems to be extensive. We are decidedly not the “Christian Republic of American States,” there is nowhere in the U.S. constitution or any of the state constitutions that mentions Christianity, and there is lots of evidence that the founders took extra steps to ensure that religion would not ever be made an explicit part of their system.

This isn’t to say that religion wasn’t important to the founding. As we saw, Jefferson and Franklin tried to put biblical allegories on the seal. And we know that most of the founders were at least nominally religious, if deistic.

BUT

And this is a big but. Just because they did their best to ensure freedom of religion and the absence of any explicit mention of Christianity does not mean that they were morally vacuous automatons. Quite the contrary, they believed that a moral code was not just important but critical to their project. And, as you might have guessed from having read my previous substack posts, they based this moral code not on religion but on an assertion of virtue.

Virtue and the founding of America

The founders may not have been writing explicitly about religion, but their work contains all kinds of references to duty, virtue, responsibility, and communal pursuit of the common good. For example, the Virginia declaration of rights states that “no free government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue.”

You should recognize these virtues from my post about virtues being the basis of good laws and the good life. The implication here is that if you don’t have solid moral foundations, you cannot have “free government” or “the blessings of liberty.” The federalist papers are loaded with passages citing the necessity of virtue. I’ll show you three of them.

Federalist 57 is a statement of the broad requirement of virtue for rulers:

The aim of every political constitution is, or ought to be, first to obtain for rulers men who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of the society.” Federalist 57

Federalist 55 is about the house of representatives. It’s a fun one to read because, at the end of it, Madison seems to be arguing against the perception that congress will become corrupt. He admits that “depravity” is possible but that there are also human qualities that justify “esteem and confidence.” I.e., humans can be bad, but can also be good. The kicker, however, is when he next admits that republican government presupposes these qualities more than any other form:

“As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form. Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealousy of some among us faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be, that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self-government; and that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another.” Federalist 55

Federalist 68 is all about the executive (the president). In it, Hamilton makes the case that, while states and localities might elect lesser men, the office of President will, due to its distinguished office, only allow success for characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue. While this seems obviously not to be the case, given the history of the presidency, Hamilton’s argument at least highlights its importance.

The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States. It will not be too strong to say, that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue.

Basically, the federalist papers are Madison and Hamilton telling us what their new system will require. And in their words, the system needs virtue to work. This obviously isn’t the same thing as religion, and it’s not a direct appeal to God or Judeo-Christian beliefs, but if you believe that one of the functions of religion is to cultivate virtues, then you might make the case that religion is at least an enabler of the system the founders conceived.

It’s not you, it’s me

In his book Democracy in America (1835), Alexis de Tocqueville asserted that the “spirit of religion” and the “spirit of freedom” are “two perfectly distinct elements.” That’s another pretty clear endorsement of the viability of the separation of church and state. But, after reading the Federalist papers’ exposes on the critical importance of virtue, it seems to me that the spirit of freedom is not independent of—let’s call it—the “spirit of virtue.”

If you take literally Machiavelli’s political design of “power pitted against power” or Fukuyama’s “balance of power,” or Madison’s Federalist 51 argument of “ambition counteracting ambition,” you might think that it is possible for completely depraved, morally vacuous, power hungry denizens to occupy positions of leadership in America and that the system would still work by having two opposing forces brutally ramming into each other. But this is not the case, and the founders knew it. And they wrote about it. The American system needs virtuous individuals at all levels for it to function. And if office holders aren’t virtuous, say the founders, then we shouldn’t expect the system to work. (If you think our system isn’t working then ask yourself whether you can name any virtuous politicians)

At the top of this post, I asked whether religion was a critical substrate on which America is built. The problem with this question is that it is a leading question. It presumes that religion is the lynchpin that holds everything together. What I propose instead is that virtue is the lynchpin. The founders explicitly excluded assertions of religion, God, and Christianity at every turn they could. But they loaded the federalist papers with exposes on the critical importance of virtue and they believed that their Constitution would only work with sufficient supply of virtue.

A wellspring of Virtue?

There is a lot of hyperbole today about the decline of Christianity in America. Well, if Christianity is on life support, then the study of virtue is like a dead and decaying corpse, long passed and wholly unexamined. Almost no one talks about it. Few people strive for it; fewer embody it.

So, where does anyone find virtue? The first and reflexive answer that most of us reach for is “religion.” (haha, gotcha) Religions are organized systems of faith and worship that also, when at their best, teach virtues. For this reason, it makes sense that those who lament American dysfunction would reach for religion. And, given that Christianity specifically was widespread at the American founding, it makes sense that Christianity would be the choice solution to our current political malaise. But are modern Christians really known for balancing wisdom and moderation? (Are any moderns known for balancing wisdom and moderation?) I would say not.

We’ve already established that the founders didn’t explicitly favor religion, and for this reason, I don’t think we should explicitly favor it today either.

Fortunately, religion doesn’t have to be the only source of virtue. Let me give you a few other ideas: The Boy Scouts of America, founded in 1910, have long been a source of virtue for young men. The Scout Law, recited at the start of meetings contains 12 points: “A scout is trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent.” Not that long ago, other fraternal organizations existed for grown men as well. There was the Knights of Columbus, Rotary Club, The American Legion.

But you know something else that I seeded throughout this piece? Many if not most of the founding fathers were freemasons. And it turns out that the freemasons are a fraternal (men only) organization dedicated first and foremost to cultivating virtue and high moral standards. The freemasons have three key tenets:

Brotherly Love: A true Freemason ought to show tolerance and respect for the opinions of others and be kind to and understanding of his fellow human beings.

Relief: Freemasons are taught to practice charity, not only for their own, but also for the community at large.

Truth: Freemasons are taught to search for truth, requiring high moral standards and aiming to achieve them in their own lives.

Ben Franklin was a freemason for 60 years, the grandmaster of Pennsylvania, and apparently only missed 4 lodge meetings in his entire life. George Washington, acting as grand master pro tem, presided at the Masonic ceremonial laying of the United States Capitol cornerstone. These guys weren’t just members, they were the leaders of a fraternal organization aimed at virtue. And George Washington, serving as a grandmaster, laid the cornerstone of our capitol in a masonic ceremony. Does it get any more symbolic than this?

And by now you are probably tired of hearing about connections to the ancients, but get this: Plato’s philosophy is at the core of freemasonry. In fact, freemasonry is sometimes called “the religion of Plato.” And lest I remind you, not only is pretty much everything Plato wrote in some way about virtue, but he wrote about it long before Christianity even existed.

Make of this what you will, but I think that modern arguments that connect the decline of Christianity with the dysfunction of America are a red herring. The founders wanted all Americans to have complete freedom of religion. But prudence, courage, temperance, and justice were non-negotiable. The freemasons, by the way, still exist.

As I’ve said in my other posts and in my about page, I am not a lawyer. So, come at me if you are upset, but if you do so, please do so with the proper balance of music and gymnastics.

There are however eight state constitutions that prevent atheists from holding office: Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas. These clauses have never been tested and would almost certainly fail under Article 6 of the U.S. constitution.

And if you really want to go down a Dan Brown rabbit hole, check out The Illumaniti. The organization was founded in 1776 with the stated goals of opposing superstition, obscurantism, and religious influence over public life. It has been accused of (or credited with) masterminding world affairs from behind the scenes, and along with the Freemasons, it has strong links to early America.

Strauss at least makes a case for this in Natural Right and History.

Furthermore, Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration is, as its title suggests, a long argument for religious toleration. He was writing in a time when Christians were killing other Christians who were killing “Moslems” and vice versa. The whole piece is just Locke saying over and over that this is dumb. And that he thinks we should allow religious groups to just do what they want to do.

The outcome of all of this action was that both phrases, “In God We Trust” and “E Pluribus Unum” were now required to be inscribed on all U.S. currency. And today, you can see both of these on the dollar bill.

Many interesting details here, Rudy. Gives me plenty to think about.

I think it’s worth noting that Freemasons require members to believe in the existence of a supreme being and the immortality of the soul.