The School of Athens - Raphael (1511)

For most of my 20s, I lived in Boulder, Colorado, a town of professional athletes—mostly rock climbers and endurance athletes. Most of these people love what they do—they love training and they love competing. When their career winds down, some gracefully transition to coaching or a new career. But some really struggle figuring out what to do next.

And to be fair to Boulder, people in other careers and sports and hobbies also struggle to get past their own pinnacles of modern “meaning” and “high achievement.”1 For example, the insurance executive who works 80hr weeks until the day he dies at his desk. Or the 30-yro dude who still lives in the frat house glory of his ability to drink 30 beers while not dying.

Anyway, I recently talked to a Boulder friend who is nearing the end of his professional rock climbing career and is struggling a bit with feelings of depression, aimlessness, meaninglessness, and nihilism. You probably don’t have to think very hard to come up with someone you know who is or has struggled with these same problems of existential crises or meaning. Lots of moderns are struggling to figure out how to live and what to live for.

We want to live for something

Now, as everyone knows, the easiest way to solve these problems is by purchasing a boat. If you can’t afford a boat, other less expensive “treat yoself” options include simple luxuries like a spa day, buying a new pair of shoes, or taking a vacation where you can generate cool photos for your Instagram.

Of course, once you find out that dopamine hits of stuff and experiences are not enough to give your life meaning, you might try to find it in your career, whether that is through a job that makes you feel “important,” or “needed,” or like you are doing something “meaningful,” or because it is making you filthy rich. Recent college graduates reach for all of these. So do people in mid-life crises. And maybe these things will make you feel great, for a bit. But they too will fail. When this happens, maybe you will search for the next thing. And do this until you die.

Modernity is supposedly the best time to be alive. That’s pretty interesting considering how many people are struggling to find a point of being alive. And yes, there is no question that people have more material wealth, luxuries, and satiation than ever before. But does that make our lives good? Is there something better we could be aiming at?

The good life and the mere life

The reason transition points are hard is that we humans seem to really want to live for something. We want to believe that our life has purpose and meaning. We don’t just want to be alive—we want it all to mean something.

Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle all thought that the purpose of human life was to live a “good” life. But what does it mean to live a “good” life? Certainly no one tries to live a bad life. And plenty of moderns think their lives are pretty good. But the ancients meant something specific: it was the difference between mere living and living well.

“So examine again whether or not it still holds true for you, that it's not living that should be our priority, but living well.” Plato Crito 48b

The idea is, incidentally, also captured by Nicki Minaj in the song Moment 4 Life.

I am no longer trying to survive,

I believe that life is a prize,

But to live doesn't mean you're alive.

The reason I’m bringing Nicki into this is that she shows that humans of all eras (Nicki to Plato) are, at least on some level, sensitive to the fact that merely being alive is inadequate. Everyone seems to agree that there is something more we should be aiming at.

Now, the challenge with Nicki is that, although she seems aware that mere life is inadequate, we have no indication as to whether she knows what is adequate. And I’m sorry to report that, if you read her lyrics, you aren’t going to find answers.

However, if you read Plato…

Aiming at the highest good leads to the best life

One of the most enduring philosophical questions in my life is the question of modern nihilism. In an age where ultimate meaning is stripped from the world, many modern people succumb to a sense of hopelessness in the perceived meaninglessness.

The thing is, if you are alive—if you have not killed yourself—then you are by definition asserting that there is something worth living for—that there is at least one reason to live. And no matter what that reason is, even if it is something totally base like wanting to vape as many of those versions of those candy flavored pods as possible, you can probably think of better and worse ways of doing it.

Let’s say your one reason to live is “pleasure.” It would make sense that you would aim at the best way to live pleasurably. But, what is the “best” ratio of hedonistic pleasure to the pleasure of accomplishment? And, within hedonistic pleasure, what is the “best” amount of sex, drugs, and music festivals?2

Aristotle reasoned that every action we take is aimed at some good. And if we put all those actions together, we can conclude that all actions are aiming toward some highest good which is the object of all our aims and longings. This highest good is the ultimate thing that we are aiming at.

“Since all knowledge and every choice have some good as the object of their longing—let us state what it is that we say the political aims at and what the highest of all the goods related to action is. … it is pretty much agree on by most people; for both the many and the refined say that it is eudaimonia, and they suppose that living well and acting well are the same thing as being happy.” - Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Book 1 Chapter 4

According to this quote, if we sufficiently aim at that overall highest good, we can achieve a state of “Eudaimonia” — something like a combination of happiness and flourishing.

Thus the reason we aim at the highest good is not because we want to be good. It’s because this leads us to the best outcome—to our highest happiness and our greatest flourishing. The point is: aiming at the highest good > the good life > eudaimonia.

So, what is the highest good?

The highest good is a life of virtue

Today we think about virtue as a term synonymous with being a “good person.” On the political left, virtues include things like empathy and care. On the right it includes things like resilience and respect. (Just the fact that modern virtues differ based on your political affiliations should tell you that there is something wrong with our modern conception of virtue).

And sure, we all want to embody these qualities… sort of. But, if you’re having an off day and don’t feel like being polite, that’s fine. No one will punish you if you aren’t. Life will go on. It’s like we still recognize the existence of virtue, and we nominally value it, but we don’t put any weight behind it. In America today, virtue is sort of a take it or leave it kinda thing.3 John Steinbeck wrote about this when he drove across America in 1962.

“We value virtue but do not discuss it. The honest bookkeeper, the faithful wife, the earnest scholar get little of our attention compared to the embezzler, the tramp, the cheat.” Travels with Charley: In Search of America

By contrast, the point of virtues for Plato and Aristotle was not to “be a good person.” And the cultivation of virtue wasn’t a side project, take it or leave it. Virtues were about guiding you toward a better life. I.e. a life aligned with virtues was a pathway to the best life, or the life well lived. The reason they thought you should live a virtuous life was because that was how you oriented yourself on the path to eudaimonia—the pinnacle of happiness and flourishing.

“We are conducting an examination, not so that we may know what virtue is, but so that we may become good.” - Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Book 2 Chapter 2

Thus, the highest virtues > aiming at the highest good > the good life > eudaimonia.

But, of course, there are several challenges of living a life of virtue. (1) We need to know what the best and highest virtues are, and (2) we need help cultivating these virtues and aligning our actions with them.

Good laws produce the best virtues

You’ve probably heard of Aristotle’s golden mean—that the virtue is found between the extremes. Courage, for example is the mean between cowardice and rashness. Ambition is the mean between sloth and greed. And so on.

“In everything continuous and divisible, it is possible to grasp the more, the less, and the equal, and these either in reference to the thing itself or in relation to us. The equal is also a certain middle term between excess and deficiency.” Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Book 2 Chapter 6

This assessment offers a starting survey of the landscape of virtue. But there is also a hierarchy of virtues with four cardinal virtues at the top. These are: prudence, justice, temperance, and courage. They were first described by Socrates in The Republic.

“I suppose our city—if, that is, it has been correctly founded—is perfectly good … is wise, courageous, moderate, and just.” Plato The Republic 427e

In fact, much of what the Socratics were writing about had to do with virtue in one form or another. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is obviously about ethics and it is the foundation on which The Politics is written. The Laws of Plato is largely a meditation on ethics and social psychology, and The Republic is actually an investigation of the question of justice.

This foundation of modern ethics can be traced from the ancients all the way to modern liberalism. Saint Augustine, the greatest Christian thinker of antiquity (~400AD) had a well-documented relationship with Plato. Saint Thomas Aquinas (~1250) leaned heavily on Aristotle. And of course, Christianity was the religion on which western liberalism was built. The virtues that were espoused by the Socratics were undoubtedly woven into the foundation of America.

And if you pay attention, you can find evidence of this influence built right into the façade of modern buildings—modern government buildings. It’s usually the four cardinal virtues.

Statues of the four cardinal virtues outside the courthouse of the City of Bergen, Norway

The reason for this is simple: if you want your citizens to live the best lives possible, then ostensibly, (if you believe the ancients), you want to enable your citizens to live their lives in alignment with the highest virtues. And in order to do this, you need to write laws that also align with the highest virtues.

“Looking back over all these things, the one who frames the laws will set up guards—some grounded in prudence, others in true opinion—so that intelligence will knot together all these things and may declare that they follow moderation and justice but not wealth or love of honor.” Plato The Laws (632c)

Now we have a complete picture of how the ancients thought about living a good life. It started with creating laws that enabled the highest virtues which led to the highest goods, the good life, and ultimately the greatest happiness and flourishing of its citizens: the best laws > the highest virtues > aiming at the highest good > the good life > eudaimonia.

This all sounds pretty straight forward. And if it’s true, then it seems like our goal should be to create laws that aim us toward the highest virtues so that we citizens can live the best lives of happiness and flourishing.

That, however, doesn’t sound much like our modern system. Our laws are often petty and political, we talk about virtue only fleetingly, and plenty people seem to be neither aimed at nor in attainment with eudaimonia. Where did things go off the rails? I think the breakdown centers around a devaluation of virtue.

Modernity

The moderns ditch virtue

The most pronounced difference between the ancients and the moderns is in our relationship with virtue. As we saw above, the ancients studied virtue in great depth and they nurtured it as a path to the good life. We moderns consider virtues to be optional, contingent on our politics, and defined by meaningless slogans like “just be a good person” which is about as useful as putting someone in the cockpit of an F-35 and saying “try hard.”

The shift began at the end of the middle ages with Machiavelli.

“The fact is that a man who wants to act virtuously in every way necessarily comes to grief among so many who are not virtuous. Therefore, if a prince wants to maintain his rule he must be prepared not to be virtuous, and to make use of this or not according to need.” “He must not flinch from being blamed for vices which are necessary for safeguarding the state. This is because, taking everything into account, he will find that some of the things that appear to be virtues will, if he practices them, ruin him, and some of the things that appear to be vices will bring him security and prosperity.” Machiavelli The Prince Ch 15 (1532)

In short, says Machiavelli, no one is perfectly virtuous. But, unlike the ancients who wanted to try to aim in that direction, The Prince should make use of his virtues and vices because any of them could be useful. In short, Machiavelli lowered the standard of virtue in order to achieve results.

Suddenly, modernity was born. Productivity began to increase. We “broke free” from the “dark ages.” We freed ourselves from the binds of religious conformity. We began inventing new technology. We started to grow wealthy. We began a path toward liberalism. As I’ve written elsewhere, this shift led to Hobbes, Locke, and pretty much every other modern political philosopher.

Classical views of virtue hung around as ideas always do, but these men, their systems, and the people who lived in their systems, became increasingly alienated from the ultimate good because they were, simply put, not aiming at it anymore. They were instead aiming at outputs like wealth, property, individual liberties, equality, and less war and death.

Men without chests

Take Thomas Hobbes, a modern political philosopher who is remembered for declaring the state of nature “nasty, brutish, and short.” Hobbes sought to avoid this “state of nature” with a strong, unified government.

In Hobbes’ conception of the world, people are inherently barbaric. But rather than cultivating virtue as had been recommended by the ancients, Hobbes thought it better to create a social contract: an implicit social agreement where people sacrifice some individual freedom to the state which in turn provides law, order, and protection.

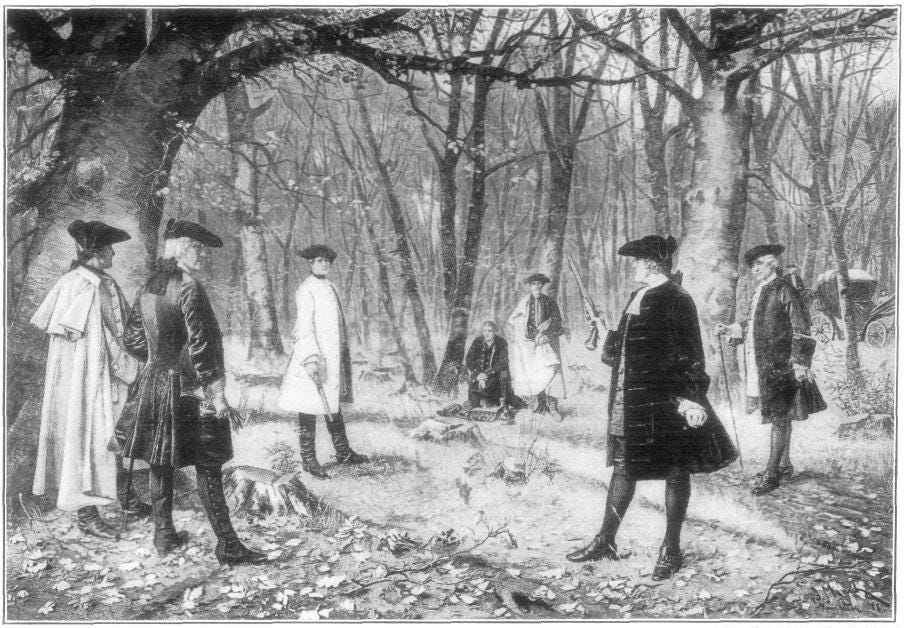

In such a system, the cultivation of virtue is largely superfluous. Sure, it’s nice if people are “good”, but it doesn’t really matter because the state is there to keep them in line if they aren’t. In this system, the cultivation of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance seems quaint. Take honor. People were once willing to die over their honor. Alexander Hamilton died in a duel over honor (picture below). Personally, I’m not sure there is anything I die in a duel over.4

It seems Hobbes felt the same. He wrote that he was “the first of all that fled,” at the outbreak of the English Civil War, doing so “not out of treachery, but fear.”5 By all accounts, he was a rational atheist who couldn’t see the value in an “irrational” bloody conflict.

This comment makes him sound a bit like a pu$$y, but to his credit, he was acting in a perfectly modern way. To us moderns, war and death are so obviously bad that we reject them almost without even thinking. After all, if you believe that this life is all their is, you will almost certainly be tempted to cling to it. You might do anything you can to preserve it.6

It was this temptation to cling to life that made Hobbes so desperate to flee the state of nature for the warm security of a strong paternalistic state. In his Leviathan, there would be rules and a unified government. In his view, it wasn’t rational to leave people to their own devices. The state would hold people in check. It would prevent them from killing each other, from going to war, and from accidentally killing themselves. The Leviathan ordered our lives to preserve our lives. That was the point. It was an early case of the very modern trade of freedom for security.

We pay for security with our souls

But what Hobbes glosses over are the costs we pay to preserve our lives. We trade temperance for wealth. This buys us unprecedented healthcare and longer lives. We trade courage for security. This makes us safe but soft. We spurn justice and prudence when it serves our aims. In short, we trade virtues for mere life. In the modern view, these are all rational choices.

But to the ancients, Hobbes was missing the point. Agamemnon didn’t invade Troy because it was rational.7

To fear death, my friends, is only to think ourselves wise, without being wise: for it is to think that we know what we do not know.” Plato Apology 29a

The result is that many modern people are perfectly physically satiated. We live in perfectly conditioned living quarters. We have unlimited access to Netflix, sports, porn, and an endless supply of door dash. But because none of this is aimed at virtue, our metaphysical existence is like a rotting pile of garbage. Eudaimonia is probably not even possible.

And we’re lost

Drake concludes the song Moment 4 Life with the line:

I'm really tryna make it more than what it is, cuz everybody dies but not everybody lives

As I said at the beginning, it’s encouraging that a thymotic anthem with millions of streams makes reference to the inadequacies of mere life. But just because moderns recognize the inadequacies of mere life doesn’t mean we know where or how to aim otherwise.

Drake and and Nicki spend their entire Moment 4 Life music video completely and predictably blinged out with fancy clothes and décor and golden everything. Nicki says “I get what I desire, it's my empire.” Drake: “What I tell 'em hoes? Bow, bow, bow to me, drop down to ya knees.” Prudence, justice, temperance, and courage are nowhere to be found. Obviously I’m being somewhat snide in my analysis of Moment 4 Life, but it is kind of funny to watch people at kindergarten levels of virtue brag about “truly livin’.”

I don’t even mean to pick on Drake and Nicki. They are just a mirror for the rest of us. We are, as a society, right there with them. One way you can tell that we aren’t aiming at virtue is that, at the end of life, westerners, even rich and famous people (maybe especially them) report wishing they had spent more time with family and friends, that they had not worked so hard, not worried so much about money, and that they had let themselves be happier. Sounds like they wish their life were a little more focused on prudence, justice, temperance, and courage. Crazy.

One of the themes of The Republic is that the city is a mirror for the individual.

“I’ll tell you,” I said, “There is, we say, justice of one man; and there is, surely, justice of a whole city too?” “Certainly,” he said. “Is a city bigger than one man?” “Yes, it is bigger,” he said. “So then perhaps there would be more justice in the bigger and it would be easier to observe closely. If you want, first we’ll investigate what justice is like in the cities. Then, we’ll also go on to consider it in individuals, considering the likeness of the bigger in the idea of the littler?” Plato The Republic (368e)

I.e. our city is reflected in our individuals. Today, we have lost sight of virtue at the level of the the individual and also at the level of the republic. We (1) have laws that are not aimed at virtue (2) have society that is not aimed at virtue (3) we don’t know what virtue is (4) even if we did know what it was, we aren’t aiming at it anyway. In sum, it’s a real shit show out here in modernity. And it’s hard to know where to try to fix it.8

The mere life

I recently read an article about the modern meaning crisis. The author argues that the flood of information is triggering a crisis of epistemology (how we know what we know) and that this is triggering “everyone’s existential crises.”

There’s definitely some truth to this — that the flood of information is drowning and confusing and confounding us. And it’s a great article and I’d recommend reading it.

But I think it is missing a core problem. Sure, we live in a deluge of information. But I think humans have always lived in a flood of information. What has changed is not the flood, but our ability to see what matters.

Take your favorite professional athlete. This person is being flooded with yelling fans, high speeds, and a constant stream of information. But what makes them great is that they aren’t distracted by any of this. All of the superfluous information seems to fall away. It doesn’t touch them. They are calm. They see only what matters—a ball or a puck or a goal. They are focused only on what matters.

I’d say that this is the real problem with modernity. Not that we are drowning in information but that we’ve lost the ability to see clearly what really matters. If we could re-gain that skill, and re-aim our lives at virtue as a path to the good life, all the superfluous stuff of modernity would fall away and we’d be left with a clear, calm, simple unobstructed line of sight through what matters and straight at the good life. Maybe some people would even find eudaimonia.

Or, you can just buy a boat and hope for the best.

I put these in quotes because, over the course of this piece, I am going to challenge whether they are actually meaningful.

And if you decide that you want to go to as many music festivals as possible, how should you “best” make the necessary money? Etc etc.

And instead of highlighting virtues, our society is constantly spotlighting movie stars on fancy yachts, people who are famous for being famous for drinking too much and doing regrettable, tabloidable activities, billionaires with mansions, athletes with supermodels, leaders who lie, activists who use the auspice of “justice” to achieve their social agenda, etc etc. Modernity is a constant stream of perverted virtues and excesses.

Honor is an easy virtue to pick on because it has been so thoroughly eliminated from modern culture. But other virtues like courage, temperance, prudence, justice, and fortitude are equally endangered. Intellectuals, elites, and today’s leaders seem especially incapable of discussing or deploying these virtues with any seriousness.

And yet, even if you are desensitized to the meaning or use, I think most people can still sense the power behind these words. Fortitude is still celebrated in athletes and strivers in society. Prudence is recognized in the greatest investors. Courage is still celebrated in business. But you’ll never find it mentioned in performance reviews. Isn’t that interesting.

Leo Strauss Natural Right and History p197

Previously, people believed in heaven. And if you believe that this life is just a warm up round for the ultimate life of eternity in the next world, then there is nothing to fear.

But, with the “death of God,” a new era began that was characterized by the fear of death. In my opinion, the modern fear of death is one of the most psychologically interesting and societally warping forces of modernity. It’s a topic that I plan to cover in depth at a later time.

Unless you believe Marathe’s arguments in Infinite Jest (which perfectly capture the rational, measured, calculated, and modern way of understanding reality. “Marathe rose slightly on his stumps in the chair, showing some emotions at this Steeply. 'I am seated here appalled at the naïveté of history of your nation. Paris and Helen were the excuse of the war. All the Greek states in addition to the Sparta of Menelaus attacked Troy because Troy controlled the Dardanelles and charged the ruinous tolls for passage through, which the Greeks, who would like very dearly the easy sea passage for trade with the Oriental East, resented with fury. It was for commerce, this war. The one-quotes "love" one-does-not-quote of Paris for Helen merely was the excuse.’”

One area to focus could be on our laws. The Catholics say “the law is a teacher.” The meaning of this is that the law teaches you how to be—it teaches you virtues. Take legalization of Marajuana. Us moderns say things like, “legalize it—it’s not that bad” and “people would smoke anyway.” The ancients would take a different tact—they would simply ask whether legalization will push you toward or away from virtue.