Historicism, natural right, and an explanation for why modernity struggles with nihilism

Are we heading somewhere good? Are we heading somewhere at all?

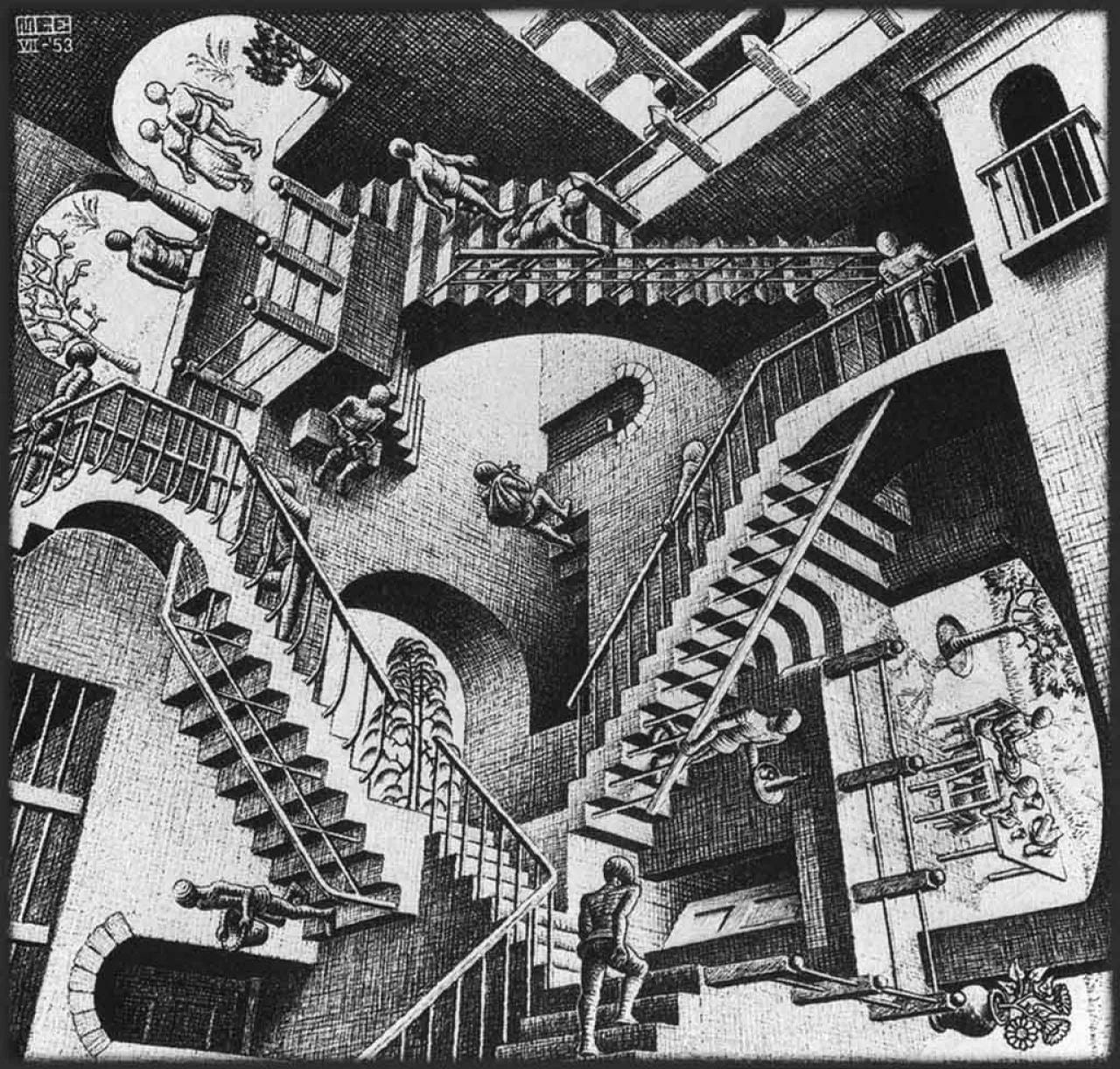

Relativity - M.C. Escher (1953)

History is clearly useful. We can place events on on a timeline and remember them in relation to each other. For example, the colonists, tired of the “tyranny” of King George III, endowed with a rich new land, and the latest philosophy of liberty, declared themselves independent in 1776 and fought the revolutionary war (1775-1783). They next adopted the articles of confederation (1781) which was later replaced by the U.S. constitution, a document that was a philosophical treatise as well as a compromise of delegates from 13 very different U.S. states (1789).

Let’s keep going. France supported the colonists in their war (1770s-1780s) because they were fighting France’s rival, Great Britain. But, supporting America was expensive and France incurred significant debt which soon led to the Financial Crisis of 1786 and the French Revolution in 1789.1

In just 2 paragraphs, I’ve told you about several major political events of the 18th century. But, I’ve done something else as well. I’ve linked them together in a historical manner. I’ve even suggested some contingencies. For example, if European intellectuals such as Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau had not been churning out new ideas about liberalism, the Americans may not have been so philosophically emboldened in their revolt. If the French had not been at such odds with Britain, they might not have helped. And if all of this had not happened as it did, maybe we would not have the United States as we know it today.

In this telling, the U.S. is not a pure set of ideals dropped from the heavens, but a product of the events surrounding its founding. In this telling, the U.S. is, at least to some extent, based in the ideas and contingencies of the times.

If we look across history, we can tell stories of contingencies about the founding of Rome, the Ottoman Empire, the Qing Dynasty, The British Empire. Looking to more recent history, we can tell a contingency story about the origins of the modern “isms” including communism, socialism, fascism, and liberalism and their instantiations in modern nations. Each evolved out of the time and place and pressures of its era.

This way of understanding the sequential regimes of history is called “historicism.”

Historicism is an approach to explaining the existence of phenomena, especially social and cultural practices (including ideas and beliefs), by studying their history; that is, by studying the process by which they came about.

In the example I mentioned above, the founding fathers instantiated a liberal democracy as a reaction against the tyranny of King George. Similarly, the Bolsheviks united workers to combat the oppression of capitalists and to instantiate a system that elevated the workers. You might even see your own party proposing a new vision for America that is more aimed at “equity” or at “freedom” or “the family.”

Each new system tries to assert something better than the past system, perhaps to correct its ills or to go in a different direction. Whatever the reasons, in following its path, we reveal ourselves as beholden to the latest zeitgeist. Today’s politicians might be calling for “equity” whereas 30 years from now they will be calling for “freedom.” This process could go on for, well, forever. Each moment is a stop on a journey with no end.

But if that’s the case, are any of our political systems and ideals actually true? Or are they just popular today? And if they are so flexible, are any of them worth believing in? Are any of them worth dying for? In the historicist framing I’ve given so far, the answer is no. It’s all relative. And this leads straight to nihilism.

Over the course of this piece, I am going to offer a potential way out.

Historicism

The "historical” view of political philosophy began in the 1600s, just as the enlightenment was taking off. People began speaking about “the spirit of the time” and the “philosophy of history” (WIPP p58).2 Hegel, one of the first and most famous historicists, prosed a historical process of “thesis-antithesis-synthesis” where an initial assertion of a political way of being is made (the thesis), followed by a correction (antithesis), and finally a synthesis of the positions. This could then be iterated over and over.

The conclusion of this historical progression was what Hegel called “the end of history.” By this, he meant that societies and political structures would evolve over time toward a final end state. Many other historicists have followed Hegel including Marx (who believed the end state was the ultimate triumph of the proletariat) and Frances Fukuyama whose 1992 book titled “The end of history” makes the case that all historical activities have been leading, in the end, to liberal democracy.

An objection to historicism

Leo Strauss was a Jewish-German-American political philosopher who came to the U.S. during the 1930s and eventually landed at the University of Chicago.

For Strauss, historicism was a byproduct of social science positivism and the incursion of “methods,” especially empirical methods, into the political philosophy. Historicists, in his view, want to see the course of history as a big empirical study on how humans organize themselves.

In contrast to this view, Strauss thought that political philosophers should use reason to make value judgments of what constitutes “the good” and then structure their political systems in light of this knowledge.3 He wanted us to think about what constitutes “the good” rather than waiting for it to reveal itself through a blind march into an unknown future. And if we do this properly, we can discover “natural rights” or so-called “unalienable rights.” Rights that apply to all humans in all times and places.

Historicism rejects the question of the good society, that is to say, of the good society, because of the essentially historical character of society and of human thought: there is no essential necessity for raising the question of the good society; this question is not in principle coeval with man; its very possibility is the outcome of a mysterious dispensation of fate. (p26)

I.e. if we don’t use reason—if instead we take the historicist approach—we leave ourselves open to a “march of history” that may not go where we want it to go. Strauss was particularly harsh about this. For example:

It was contempt for these permanencies which permitted the most radical historicist in 1933 to submit to, or rather to welcome, as a dispensation of fate, the verdict of the least wise and least moderate part of his nation, while it was in its least wise and least moderate mood, and at the same time to speak of wisdom and moderation. (WIPP p27)

I.e. only a historicist could see the rise of Nazism in 1933 Germany as “wise” and “moderate,” and, ala the historicist approach, inevitable. Yikes. Historicism is like being strapped to a rocket ship with an unknown destination. You can perhaps hope for a favorable destination, but there is no guarantee you won’t have a few evil stopovers along the way.

And that’s certainly a big problem with historicism. But the other major problem that I pointed out at the start of this piece is that historicism is, because of its endless wandering, nihilistic.

Progressivism

Progressivism cleverly seeks to combat the nihilism of historicism by asserting a positive valence to it. I.e. we may be strapped to a rocket ship that is heading aimlessly into an unknown future, but if we convince ourselves that that this unknown future is “good” then we can again believe that there is a purpose to our existence—we can again feel that there is meaning to our lives. We can believe that the wandering historicism is ultimately leading somewhere.

The idea here is captured well in MLK’s famous quote: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” With this frame, the universe is “bending” in a certain direction, and that direction is implied as good (justice).

Similarly, when you hear someone say “get on the right side of history,” they are making an appeal to the historicist approach and the subset of it that is progressive—they are asserting (1) that history has a directionality and (2) that that directionality is “good” and (3) that you should be on that side.

This type of historicism can be admirable in its faith in the future. That faith has given disadvantaged groups the strength to keep fighting for rights, knowing that justice will eventually bend in their direction.

But in taking this approach, progressivism exposes itself to the atrocities of history. If historicism is being strapped to a rocket ship with an unknown destination, then progressivism is that same situation but with a blindfolded rider convincing themselves that the destination must be a good one. Even if the rocket ship ends up in hell itself.

A real world example of progressivism gone awry is the Armenian Genocide, perhaps the most “successful” genocide of the 20th century, which succeeded in killing off about 1 million Armenians and doing so with such efficiency that for many years there weren’t enough survivors to even complain about it. The genocide was committed by a faction of the Young Turks called The Committee of Union and Progress who ostensibly believed, in their blindfolded state, that they were riding the wave into a better future.

Such atrocities also, inevitably, strip progressivism of its claim to overcome nihilism. If you have elevated yourself from the pit of nihilism by believing that the progress of history is “good,” then the only way you can keep yourself out of the pit of nihilism is to ignore the inevitable evils as the unguided rocket ship hurtles into the future—because if you take a moment to stop and look at the atrocities, then you will be forced to doubt the link between “progress” and “the good.” And at that point you will fall right back into that pit of modern nihilism.4

Historicism vs Natural Right in America

I’ve just given you a lot of damning history on the side of historicism, but still I also want to give credence to historicism. The historicist Frances Fukuyama in his book The End of History makes a lot of strong arguments about the emergence, gestation, and unshakable nature of liberal democracy in our modern age. Fukuyama argues that this march of history is what led us to America today and that will sustain it forever into the future.

And it’s not just Fukuyama. America today is a historicist paradise. Progressivism is a branch of the democratic party, sure, but both mainstream parties at some level accept historicism. Obama ran against gay marriage in 2008, but only 15 years later, 70% of Americans are ok with it. Turns out, most people do think the march of history is “good” and a mark of “progress.” This includes the Republican party which is, in the mainstream, simply lagging behind the democrats in accepting the wandering fate of historicism.5

But, this is complicated because America is also founded on natural right. The Declaration of Independence opens with: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The founding fathers didn’t believe they arrived at these “truths” and “unalienable rights” by watching the meandering path of history. They postulated them based on reason, and in the spirit of natural right.

In order to understand what they meant, we need to go back to the beginning.

The classical solution

Classical political philosophy, to quote Leo Strauss, is characterized by noble simplicity and quiet grandeur. Both Aristotle and Plato followed an approach to philosophy rather than a proposition of philosophy.

Their method was thus: each started from a set of generally agreed upon premises or opinions and then argued dialectically in search of “the good.” In this sense, political philosophy to the ancients was not an assertion of a philosophy of politics, but a philosophical conversation that was carried out in a dialectical manner.

The agreed upon premises were an understanding of political things that are natural to pre-philosophic life. For example, Plato and Aristotle both start many of their arguments by asserting that a certain way of acting is generally (or naturally) praised. This is taken as a sufficient reason for considering that way of acting as a virtue. Then, through reason, the philosopher can explore the edges of the original assertion and uncover the nature of things. And from here emerges a hierarchy and a classification of virtues found in both Aristotle and Plato.

The key term for Aristotle and Plato, as it is for Strauss, is “natural.”

“Natural is here understood in contradistinction to what is merely human, all too human. A human being is said to be natural if he is guided by nature rather than by convention, or by inherited opinion, or by tradition, to say nothing of mere whims.” WIPP p27

To expand on this, what is natural is that which belongs to every human being simply because they are human. Similarly, what is natural is that which occurs spontaneously in nature, outside of opinion, tradition, or whim. It can be discovered using human reason but it is based on the constant aspects of the natural world that are true in all times and places. This “natural truth” can never be altered or erased. As it pertains to human beings, it is “inalienable.” As it pertains to political theory, it asserts that there is a “good” way to create a political structure and that, even if we cannot achieve that structure, we can discover it through reason and seek to achieve it in our society.

If we take this approach, as opposed to historicism, we are faced with a crucial question: What are we aiming at?

This question is decidedly divergent from the historicist approach. Rather than strapping ourselves blindly to the rocket, the natural right approach first asks where we want to go. For the ancients, the intended destination was “the good” and the fuel to get there was virtue. And so the solution to political philosophy was to cultivate virtue in service of arriving at “the good.”

Both Plato and Aristotle follow this approach. Plato’s Republic is nominally a discourse on the ideal city, but the actual question driving the entire book is a question of the nature of justice. Aristotle takes a similar approach. He only talks about Politics after spending an entire preceding book on Ethics. Both seek to cultivate virtue in service of “the good.” 6

So far, the classical approach sounds great. And for many years, civilizations built their political structures on the strength of a virtuous ruling class.7 But this approach has at least two major practical challenges: (1) it’s difficult to keep the ruling class virtuous and (2) it’s difficult to deny everyone else the “freedom” to participate.

As time passed, these challenges overwhelmed the classical approach and modernity took its place.

The modern solution

Modern political philosophy, according to Strauss, begins with Machiavelli. The reason for this break is that The Prince (1532) focused, for the first time, on what was effective in reality rather than on the true whole of what is natural and good. Yes, said Machiavelli, it might be nice to have a guardian class that is educated in virtue, but you know what works great—harnessing the unbridled passions of the prince and using them to produce fruits for the society. Machiavelli replaced the ancients by asserting that the passion for glory would motivate the prince, in selfish interest in the preservation of his work. Machiavelli justified immoral acts by directing them toward results.

It turned out that this was very effective. One hundred years later in 1651 Hobbes took it a step farther, asserting that the selfish urges could be reduced to the desire for self-preservation (this being the goal of the social contract laid out in the Leviathan). Locke then turned the desire for self-preservation to a desire for property (as described in his Second Treatise of Civil Government). What Machiavelli turned to glory, Hobbes turned to power, and Locke turned to the right to unlimited acquisition.

And Locke, of course, along with Montesquieu, greatly influenced America’s founding fathers and the creation of the U.S. Constitution, the greatest instantiation of political liberalism the world had ever seen.

The Faustian bargain of modern natural right

But there’s a twist. For the moderns, the theory of natural right that Locke and Hobbes introduced is different than the natural right of Aristotle and Plato. Modern natural right, as we have said, detached itself from virtue and “the good” and instead focused on achieving “results” such as the protection of private property or the avoidance of death.

This is admirable in its own way. And it did achieve real results. Locke would be happy to see that his focus on protecting private property made America the most materially wealthy society in history. Hobbes also would be happy to see that, because of his focus on obviating death, relatively few people die in western systems.

But “avoiding death” or “building a lot of wealth” isn’t natural. It’s a non-human idealization of what humans could/should be, tied to mere life and comfort. By neglecting what is natural, the founders of western liberalism neglected the whole of what it is to be human. If we were all simply autistic calculation machines, we might be happy with the never-ending rise of measurable statistics in wealth, stuff, and lifespans. But as every existentialist to Dostoyevsky knows, that’s not how humans work.8

Strauss writes in Natural Right and History:

“For the modern era the notion that nature is the standard was abandoned, and therewith the stigma on whatever is conventional or contractual was taken away.” (p119)

Prior to Machiavelli, regimes at least tried to make their laws aligned with “the whole” and “the good.” Though no regime has ever achieved “natural right”9 , prior to modernity many regimes were at least aimed in the right direction. The key shift with the moderns was to remove the focus on trying to align laws with the complete, unadulterated whole of “the good.” They dropped the stigma. Instead, the moderns opened the floor and began asserting what “natural right” could or should be. Most of these guys were intellectuals, and so their ideas of “natural right” were based on ideals like “freedom” or “equality.”

The result is that the moderns became more unmoored from “natural right” and “the good” than humans ever were before. This began with seemingly innocuous laws that guaranteed freedoms for accumulating property. But now, as modern societies continue on the historicist path into an unknown future, the assertions of what should be legal continue to expand. Now, if you want to make an argument that it’s fine to cheat on your wife, you can do that. If you want to make an argument that it’s ok to schtup your dog, you can do that. Now it’s fine to do anything. If they’re ok with it, you can make it a foursome with the dog. And you can make a legal case that it’s your right, as long as everyone consents. This is liberty. Unbridled liberty. The same thing that freed us from all those pre-modern constraints.

Socrates would have looked at this situation and asked whether schtuping your dog was in service of “the good.” Far be it from me to tell you anything Socrates would have concluded, but in my own reading I think its unlikely that “the whole” of “human nature” can be reduced to mere utilitarian hedonism.

The problem with modern natural right, in detaching itself from at least trying to use nature as a standard, is that it has left itself untethered from what it is to be human. Indeed, modern natural right is the source of the nihilistic wanderings of historicism.

The crisis of modern natural right

The result is the crisis of modernity, a crisis of modern natural right. Quoting Strauss:

“Originally philosophy had been the humanizing quest for the eternal order, and hence it had been a pure source of human inspiration and aspiration. Since the seventeenth century, philosophy has become a weapon, and hence an instrument.

I’ve already told you about Hobbes and Locke wielding their systems to minimize death and maximize acquisition of property. But all the other moderns were and are up to the same thing: aiming their political structures on the ideals of the times rather than on what is “natural.” Marx and Engels focused on the equal distribution of wealth. Lenin and Mussolini focused on power. Mao on equity. Lukacs on class. Hitler on race. Etc.

Each modern, in this sense, used philosophy to accomplish the goals of the times. And each, in this sense, undermined the philosophical grounding of the ancients, obviated the quest for an eternal, divine order, and turned political philosophy into a historical meandering that was and is, in the end and again, relative, meaningless, and nihilistic.

Through the shift of emphasis from natural duties or obligations to natural rights the individual, the ego, had become the center and origin of the moral world, since man — as distinguished from man’s end — had become that center or origin.

We can feel this relativism as our global community lurches ever “forward,” pitting new systems against the old as it tirelessly searches for satiation of whatever appetitive drive matches the goals of “the times.”

What is the alternative? Is a return to ancient natural right possible? Is it desirable? Or even more frightening—as human life becomes more detached from what is natural, as the nihilism of our modern systems increasingly bites, as the crisis of modern natural right incurs deficiencies on our non-measurable spirit—do aimless modern men at some point revolt against what political theorists wish them to be and instead call for a return to a system that is actually aligned with their natural, divine nature?

A potential antidote to nihilism?

The problem of nihilism is one of being cast adrift in a meaningless universe. When we are unmoored from stable truths without purpose or direction, we succumb to a loss of meaning, a feeling that all of our actions are futile, that we are wandering aimlessly through the desert, and that everything is just heading toward the heat death of the universe. It’s a feeling that nothing matters. The antidote to nihilism is to reassert a purpose, a direction, or an ultimate anchor to our lives.

The problem of modern nihilism is one of the first philosophical questions that caught my attention nearly ten years ago. I’d read Nietzsche, Dostoyevsky, and Melville all the way to David Foster Wallace. What I wanted to understand was: (1) where does our modern nihilism come from and (2) how do we transcend it?

The question at first seemed to me be a psychological and a religious problem. After all, it seemed to begin with the 19th century “death of God” and could be traced in a straight line to modern atheism. And no doubt, one answer to the question of modern nihilism is to simply re-affirm a belief in divine law. I.e. get down on your knees and pray.

David Foster Wallace tinkered with this idea in his novel Infinite Jest. Don Gately gets down on his knees and prays to a God he “doesn’t believe in” with the faith that simply going through the motions will reattach him to a solid anchor and relieve him of the meaninglessness of life. And it does work. Kind of. It might work for you too, kind of. The problem with many modern people is that, at the end of the day, it’s hard to believe in miracles. It’s hard to believe that a few words from a priest literally turns bread and wine into Jesus. It’s hard to believe that God exists. So, while the divine law option is technically a route out of nihilism, it’s not always a useful one.

Another popular option that I described in this piece is “progressivism.” The belief in “progress” — something that can come from the right or the left. But as I showed, it too ultimately fails.

What reading the ancients showed me was that there is another potential antidote to nihilism rooted in philosophy. It is an orientation to what is natural and good. By re-aligning our political structures, our societies, and our lives to an ancient conception of “the good” we can re-discover a grounding in something that is true.

If you are reading this piece, you probably already know that I wrote a novel trying to understand the plague of modern nihilism and a solution to it. I walked up to the doorstep of an answer, and if you read it to the end, I think you will see this. The answer isn’t a statement or a fact. It may be something much closer to the ancients.

Here’s another example. Why did congress create the strategic petroleum reserve? Well, it turns out that they did it in 1975, immediately following the first oil crisis of 1973-1974, as a way to minimize future “shocks.” Prior to that, it’s important to know that the U.S. didn’t become heavily reliant on imported oil until about 1970. Gulf states had tried an embargo in 1967 that fell flat because of this. And why was the middle east suddenly a major producer and exporter of oil? The history goes on and on and on.

A great read about the history of oil is The Prize, Daniel Yergin's history of the global petroleum industry from the 1850s through 1990.

Whenever I cite “WIPP,” I am drawing from the book: Leo Strauss, What is Political Philosophy?, The University of Chicago Press (1959)

Strauss complains that positivism has “elevated scientific knowledge to the highest form of knowledge,” which leads to “complicated idiocies” and “things which every ten-year-old child of normal intelligence knows” to require scientific proof.

Progressivism is also inherently relativist in that it is self-refuting of any kind of eternal moral foundation. If you believe that your kids will have moral values that are “progressive” beyond your own, then you concede that your values are only relative to today just as theirs will only be relative to their time.

This is also why the republican political position of merely being the “brakes” on society is such a weak and indefensible position. Because it’s not a position. The democrats are correct to point out that these people are merely “behind the times.” For this reason, “Get on the right side of history” and “do it a little faster” is an easy critique of modern republicans who have already tacitly shown that they are ok with heading into that progressive future.

One consequence of this approach is that political theory based in natural right is not always savory to moderns, and no doubt, when people read Aristotle or Plato for the first time, they find that these thinkers said lots of “politically incorrect” things. For example, neither favored democracy. Instead, they favored virtue over freedom, and they thought that the best regimes for enabling virtue were the aristocratic republic or a mixed regime where an elite, virtuous class of leaders or “guardians” charted the “best” course of action for the whole politeia. One reason people love democracy is because it gives everyone a say. Plato and Aristotle would be some of the first people to tell you that “giving everyone a say” doesn’t have anything to do with whether the result will be “good” or “just.” Only a historicist could possibly entertain the thought that the meanderings of history might lead to a system that is “good” and “just.” And of course, the less “good and just” the result seems, the more tempting it will be to become progressive, and put blind faith in the hope that the outcome will eventually be “good.”

As Socrates argued in The Republic, the education of guardian class in a foundation of virtue is of utmost importance in ensuring justice of the society.

This sentence itself is an appeal to what is “natural” about humans

All laws are conventions, based in time and place. And all regimes that have any laws are based in convention. Thus all regimes with laws are “relative” and not eternal. This is why all regimes, ultimately fail. However, regimes with laws that are aimed at “the good” are at least aimed in the right direction.