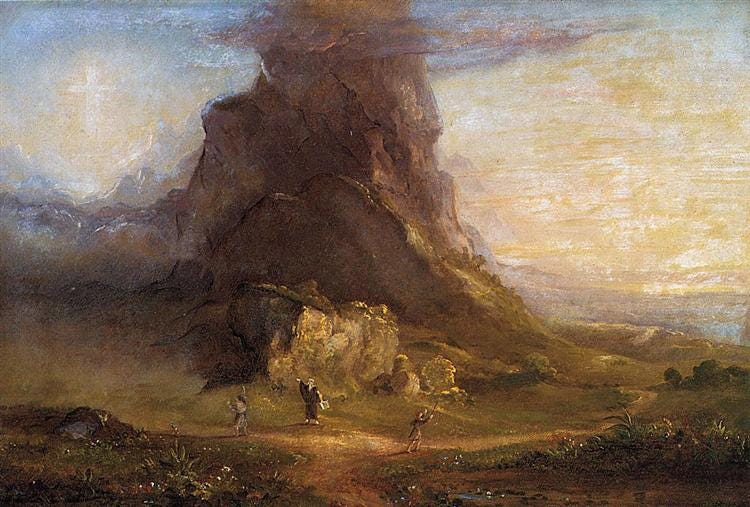

Thomas Cole - Cross at Sunset (unfinished) - 1848

I recently had the chance to travel to Catskill, New York, a small town on the Hudson River about 125 miles north of New York City. There, along with hikes and other touristy activities, I visited the home of Thomas Cole, an American Romantic Period painter and the de-facto originator of the Hudson River School Art Movement.

If you’ve been following Metis, you’ll know that I often use Romantic Period art in my posts. All of my favorite artists are from this period including Edwin Church (whose house we also visited on this trip), Caspar David Friedreich, Jasper Cropsey, Thomas Moran, John Martin, Albert Bierstadt, and of course, Thomas Cole. I suppose there are many reasons that I like these artists, but chief among them is the way they use landscapes, imagination, and subjectivity to convey exotic, heroic, sublime, and divine themes.

Cole is perhaps my favorite.

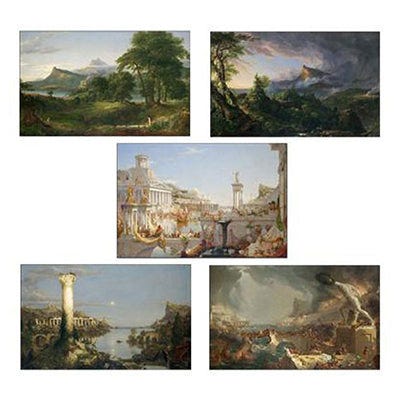

If you’ve heard of Cole, it’s probably because you’ve seen one of his multi-panel, allegorical sequences, either The Course of Empire (1833-1836), a five panel sequence of the rise and fall of an empire (above), or The Voyage of Life (1840, 1842), a four panel sequence of the course of human life (below). If you haven’t seen these, or if you haven’t heard of Thomas Cole, these sequences are worth exploring and pondering. They are filled with themes that still resonate today and details that bring you back again and again.

Cole was British by birth and came over to America in his teens, eventually settling in the town of Catskill, NY where, besides being a painter, he was a naturalist and an environmentalist. His home sits on the ridge above the Hudson river and looks west across a sweeping valley toward the Catskill mountains, which rise 15 miles in the distance. Standing there, on that porch balcony, it is abundantly clear where he got the inspiration to paint vast fields with silhouettes of distant mountains and religious themes. By his own telling, he saw in those landscapes the undefiled hand of God.

“…nature is still predominant, and there are those who regret that with the improvements of cultivation the sublimity of the wilderness should pass away: for those scenes of solitude from which the hand of nature has never been lifted, affect the mind with a more deep toned emotion than aught which the hand of man has touched. Amid them the consequent associations are of God the creator—they are his undefiled works, and the mind is cast into the contemplation of eternal things.” - Thomas Cole

At the time, the industrial revolution was booming in Europe and America. Tanners, smiths, and loggers were moving into the Hudson River Valley where they cut down trees and built new industry. Suffice to say, Cole did not much care for these activities. In fact, his inspiration for The Course of Empire came as a response to this incursion of civilization into his beloved and pristine land.

Cole’s final project

By the late 1840s, Cole had made a name for himself and young painters like Edwin Church were moving to the Catskill region to study under him. He had also just returned from his second long trip to Europe, including Italy and the Mediterranean. Back home in Catskill, he embarked on a new project, another five panel series, this time aimed directly at religious themes. It was to be titled The Cross and the World.

Sadly, he would not finish it. He died suddenly in the winter of 1848 at the age of 47 from pleurisy.

According to the docent at the Thomas Cole house, he finished three and a half of the five paintings before his death, but, also sadly, those paintings have since disappeared. Their last known location was recorded in 1889.

What did survive was five “studies” or small oil sketches of what would become the larger versions. These are the only images we have to know what the series would have looked like. There is a study for each of the first, second, third, and fifth of the series, but as far as I can tell, there isn’t a study for the fourth, or if there was, it wasn’t included in the Cole house dossier. (note that these “studies” are physically located at various museums and collections around the world).

Here are those five studies:

The Cross and The World

In the beginning of the series, in the first painting, two young “Pilgrims” are set to begin individual journeys—one toward The Cross and the other toward The World. As you can see in the study below, the route to The Cross is mountainous and uphill, while the pathway to The World descends gently downhill and into a valley.

Study for Two Youths Entering Upon a Pilgrimage

In the study for the second panel, we see The Pilgrim of The World on his journey to The World. The land is beautiful and lush and promising. Ahead is the aura of a magnificent city. In the top left we can still see The Cross, though it is hidden in the mountainous terrain.

Study for The Pilgrim of the World on His Journey

Those who have seen Cole’s Voyage of Life will have probably suspected that the magnificent white city in the distance would turn out to be a mirage. And indeed, this is the case.

In the third study, the Pilgrim of The World ends his journey in a dark wasteland of emptiness and death, which hovers in the sky as a single cloud above a dark sunset. There is not much color in the painting which creates a sense of eternal emptiness and confusion. The cross is now barely visible in the mountains.

Study for The Pilgrim of The World at the end of his journey

As I said above, I have not been able to determine whether there was a study for the ostensible 4th panel, The Pilgrim of the Cross on his journey. This seems to be the painting that Cole left for last. (More on this in a moment.)

To complete the five panel sequence, there were 2 studies that might have served as the Pilgrim of The Cross at the end of his journey. The first was specifically titled “Study for Pilgrim of The Cross at the end of his journey” while the second was only titled “Study for Pilgrim of The Cross.”

Study for The Pilgrim of The Cross at the end of his journey.

Study for Pilgrim of The Cross

In these paintings, Cole depicts the successful arrival of the Pilgrim of the Cross to a point of salvation. The light of this panel stands in stark contrast to the darkness of the final panel of Pilgrim of The World.

The first steps of The Pilgrim of The Cross

This sequence of paintings was said to be Cole’s artistic response to the tumultuous times of his era. The industrial revolution—the promise of The World— was bringing waves of new technology and the promise of progress. Atheism was surely creeping through cities, though Melville and Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche wouldn’t officially announce it for another ten or twenty years. The path of The Cross had probably already begun to seem laughable in comparison to the path of The World. Our challenge today, the choice between The Cross and The World, is the same. Perhaps the choice has only grown more difficult.

What I find myself wondering is: what did Cole imagine for that 4th panel—the Pilgrim of The Cross on his journey. When given a fork in the road where we can chose the The World or The Cross, what does the next step look like? We know that the journey to The World looks lush and promising, but what about the journey to The Cross?

My first thought is that Cole would have painted it as promising but difficult. Perhaps as a climb through the mountainous terrain. But then I wonder whether it would only look difficult from the start, and once the pilgrim embarked on his journey, it would turn out to be light and freeing.

I find myself wondering if perhaps the reason we don’t know Cole’s vision for the 4th panel—the reason he left it for last—is that it was also the most difficult for him to define. I wonder whether Cole himself, a poet, a naturalist, and a believer in God, didn’t know what that path should at first look like. Perhaps still today, like the lost sequence of paintings, what has become most obscured, most lost, is the vision of what it looks like to take that first step toward The Cross and begin a journey not toward false cities, but toward true light.

Lovely piece, Rudy. I had no idea about this “lost” series of his. Very moving to consider it.